Back in July, I fessed up to my struggle to understand current marketing definitions and boundaries in the IAM world. As part of my journey to clarity I proposed four components found in modern IAM architectures: policy, orchestration, execution, and data. I went on to then suggest, for good or evil, the notion of a workforce identity data platform which expanded on my ideas about the data tier of the modern IAM architecture. I now want to expand on the ways that you can use the four components of a modern IAM architecture to better understand your IAM world and approaches to augmenting and modernizing that world.

Using the Four Components of Modern IAM

TL;DR: you can walk through your identity infrastructure and classify what each of the pieces of infrastructure do from the perspective of policy, orchestration, execution, and data and in doing so better understand what you have, what the business needs you to have, and where you can more easily make changes.

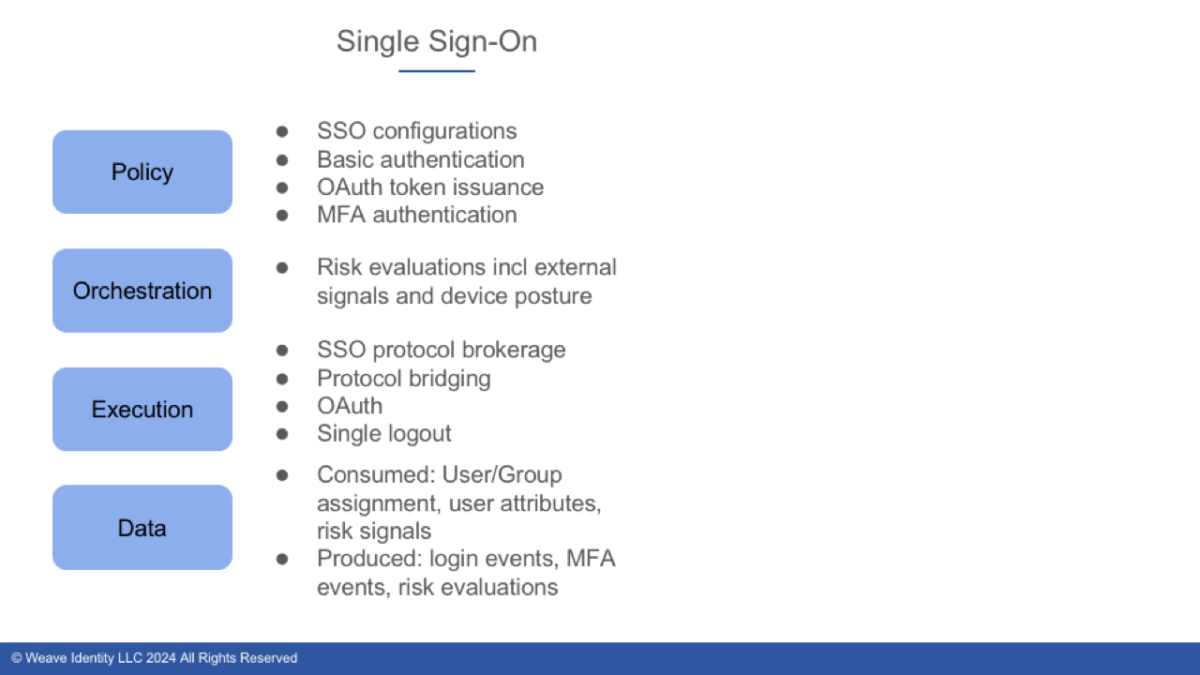

To explore how this works in practice, let’s review an enterprise SSO and evaluate it to understand what it provides in terms of the four components.

From a policy perspective, an SSO system ought to have policies that cover a variety of things. First off, it needs policies that describe the SSO configurations, including related certificates, endpoints of downstream systems, and claims requirements. It needs basic authentication rules and claims information (e.g. who can do SSO to which apps and what information about those people do we provide when they do SSO.) If the SSO system provides OAuth capabilities, then it requires policies that cover OAuth token issuance including which OAuth flows are permitted, access token lifetimes and use restrictions, and refresh token rules. Lastly, if the SSO system provides multi-factor authentication (or delegates to a system that provides it), then policies are needed to describe under what conditions a user is challenged and what forms of MFA are allowed.

From an orchestration perspective, the SSO system focuses on orchestrating risk evaluations to fulfill MFA policies which might include “outsourcing” the MFA challenge to a delegate system. It might gather risk signals from an external system; it might pull in device posture information from an endpoint detection and response system; it might also consult its own risk engine to make a final determination.

What about from an execution perspective? An SSO system brokers single sign-on including the handling of all of the applicable protocols (notably SAML and OpenID Connect) as well bridging between one protocol and another (e.g. accept a SAML inbound request and broker OIDC outbound.) Similarly, the SSO system may include a sub component that handles OpenID Connect and OAuth flows and thus requests for OAuth tokens. Lastly, it manages single logout requests, both standards- and proprietary-based.

And what of data? Well we need to think about data in two ways: data consumed and data produced. On the data consumption front, an SSO system consumes data about risk signals, user group assignments, as well as individual user attributes. It produces login and MFA attempt data as well as resource access logs; this data taken together should provide a good picture as to who is trying to access which systems.

Now as you step through this process, you’d identify which systems provide which capabilities. For example, you might have an external 3rd party risk system along with a homegrown risk evaluation engine which the SSO system would orchestrate.

With this analysis complete you’d be left with a simple chart like this:

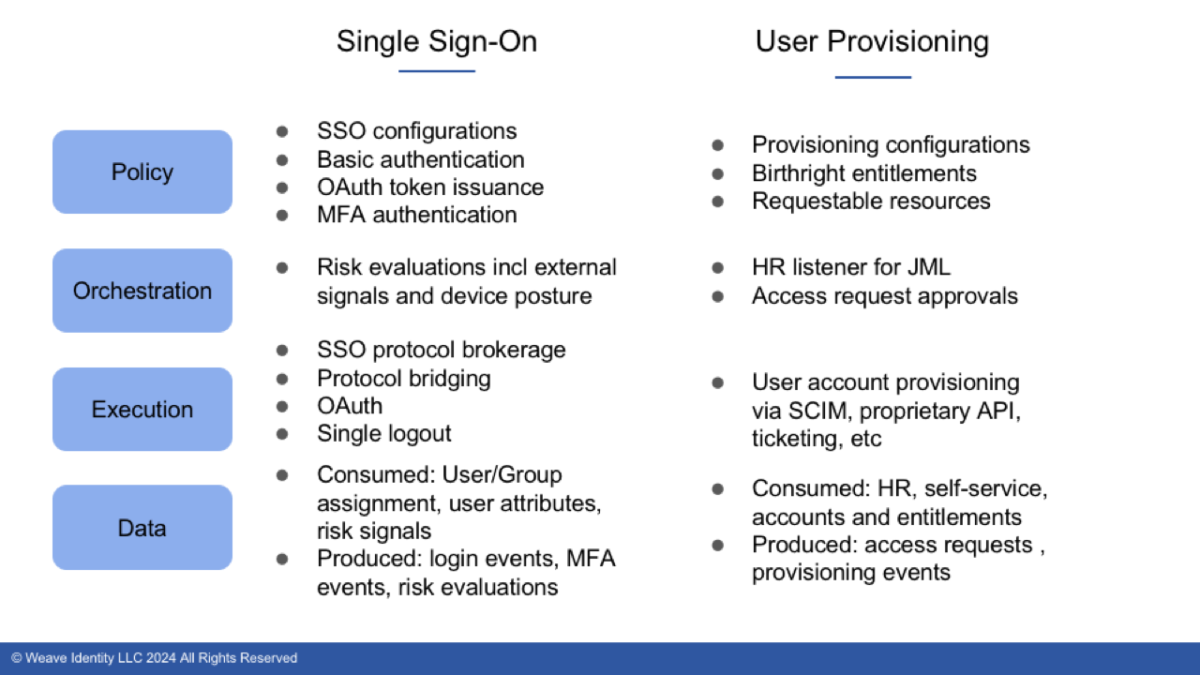

You repeat this analysis for each of your major building blocks in your identity infrastructure. Let’s do this again for user provisioning.

Policy:

- Provisioning configurations including the credentials that provisioning connectors use to automate provisioning as well as integrations into ticketing systems for manual provisioning services

- Birthright entitlements: what people are allowed to have on day one of forming a relationship with the organization

- Requestable resources: what things people are allowed to ask for in terms of systems and entitlements. For example, I am allowed to ask for a Lucidchart account but I don’t get one on day one.

Orchestration:

- HR “listening” for joiner, mover, leaver activities which detects when someone is added to the HR system and thus triggers a new user to be created or when they change job roles and their access changes or when they leave the organization and their accounts need to be deactivated

- Approval workflows which describe what happens when new or changed access is requested, either by an individual or by some machine process (such as an HR listener). Is a human’s approval needed and if so who? Is there additional information that needs to be gathered like an organizational chargeback code?

From an execution perspective, the user provisioning system manages the execution of the actual provisioning process whether that uses an automated provisioning connector or a manual approach using a help desk ticket or a combination of the two.

When we look at the data component, a user provisioning system consumes data from HR, from self-service forms, and data provided because of workflows as well as entitlement and account data from managed systems. It produces data about who asked for access to which resources as well as all of the provisioning actions (e.g. the system created a new account for Sally in Zoom; it updated Bill’s AD account and added a new group; it deactivated Jonathan’s Slack account.)

So now our analysis looks like this:

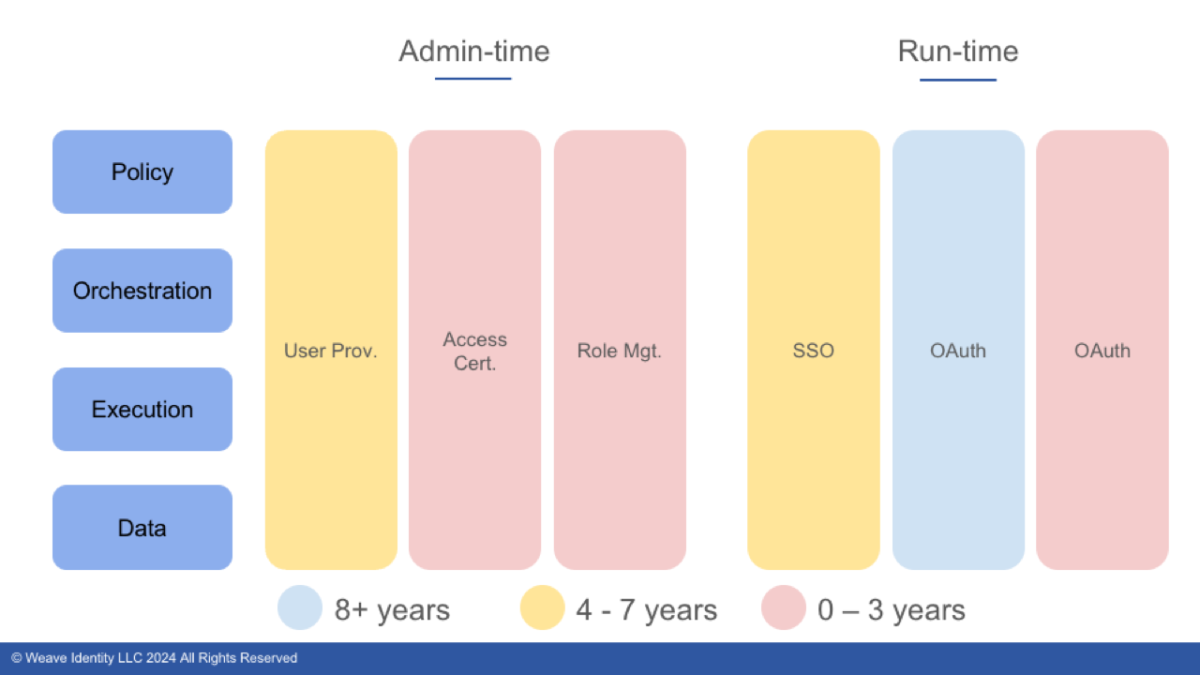

Adding Time of Use

Now the process I just described will help you build an inventory not only of identity infrastructure components but also the capabilities they provide. It will thus point out gaps you might have as well. But it is likely you might have multiple pieces of your identity infrastructure that provide overlapping capabilities. This can get a bit messy so something that can help bring a bit of order is to consider time of use. By that I mean breaking down this analysis by admin-time, run-time, and event-time systems.

Traditionally the identity world has thought of the world in two parts: admin-time and run-time. Admin-time are identity systems that do what they do before the user uses a user account or entitlement they have been granted. Run-time systems concern themselves with creating and renewing user sessions - think single sign-on and access management more generally.

The older notions of admin- and run-time is perfectly fine to start with but the reality is that there is a third category that we now can utilize: event-time. One can think of event-time IAM as the ability to apply controls to an existing, active, user session based on a signal received and processed by an identity fabric. Those controls can include terminating the session outright, revoking specific privileges, adding specific privileges, and more.

It is crucial to realize that we now have the ability to actually do event-time IAM at scale. Standards such as CAEP and the associated Shared Signals Framework (SSF) give us a “dial tone” to send and receive signals such as “password reset” or “session terminated.” Endpoint technologies give us greater insight into the security posture of the devices people are using. Modern compute and database capabilities give us the ability to reason across a variety of environmental data, not only device posture, but also business conditions. And event-processing hubs can reach out can change user session permissions.

If we apply the admin-, run- and event-time filter to the methodology we’ve been talking about now we can get a clearer picture of what capabilities you have, where overlaps exist, where are the gaps, and more.

In fact, one can go one step further.

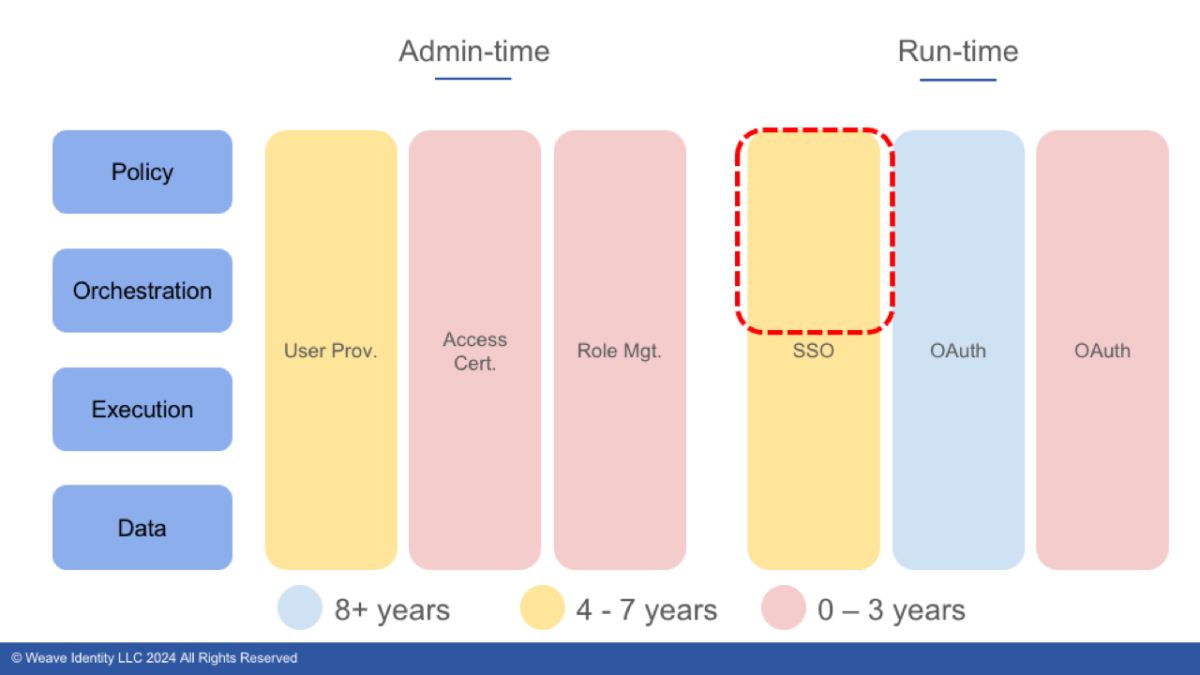

Adding replacement cycle

I believe that it takes about 10 years for enterprises to replace major identity components. The replacement cycle is somewhere in the 8 to 10 year range for an IGA system and 7 to 9 for an identity provider / SSO system. The implication is that if you have a business need that those major components do not fill you either have to wait for the vendor’s innovation cycle to catch up or you need to augment the existing service with a new one. That’s a non-trivial decision to make and it pays to give yourself a heads up that such a decision is looming.

The easiest way to do so is to add ‘years until predicted replacement’ to our earlier analysis, which will lead to a picture that might look like this:

This allows you to see which components are not going to be in scope for replacement in the coming years and which are ready to go. Now not only do you know which systems provide which capabilities in terms of policy, orchestration, execution, and data but also have a clear window into when you expect to replace that system.

You might realize that you have a gap in your SSO system related to policy and orchestration. Maybe you cannot consider as many risk signals and device posture indicators as you’d like to or it doesn’t give you the assurance and security posture you want for access to critical production systems.

Your SSO system is 5 years old. What should you do? It’s not quite at its sell-by date, but you have needs it is not meeting. You might decide to wait it out, hoping that the vendor’s roadmap catches up to your needs. You might choose to gut it out the 2 to 4 years to replace the IDP entirely (or consider accelerating replacement.) But adversaries and regulators aren’t going to give you that much time. Alternatively, you might decide to bring in a specialized IDP that can give you the risk analysis you want and chain the new IDP to the incumbent one, thus augmenting its capabilities. Regardless of the choice you make - this methodology helps you see your needs and options a bit more clearly!

Getting to work

Not only are the boundaries that define traditional IAM markets a bit blurry, where organizations are sourcing their IAM solutions. Given the earlier observations about replacement cycles, I see organizations more willing than ever to augment incumbent components of their identity infrastructure with focused, fit-for-purpose solutions instead of rushing to replace those incumbent solutions.

It’s an interesting time in the market in that regard. There is a return to the old “best of platform” approach which has ended poorly not once but twice. And at the same time, we see more entrants to the market than ever. Regardless of your approach to sourcing identity capabilities, the model presented here enables you to hold fast to the capabilities that the components of your IAM infrastructure provide, against the backdrop of time of use, and replacement cycle. And in this regard, you too can put the four major components of modern IAM to work for you!